Surgical Sutures

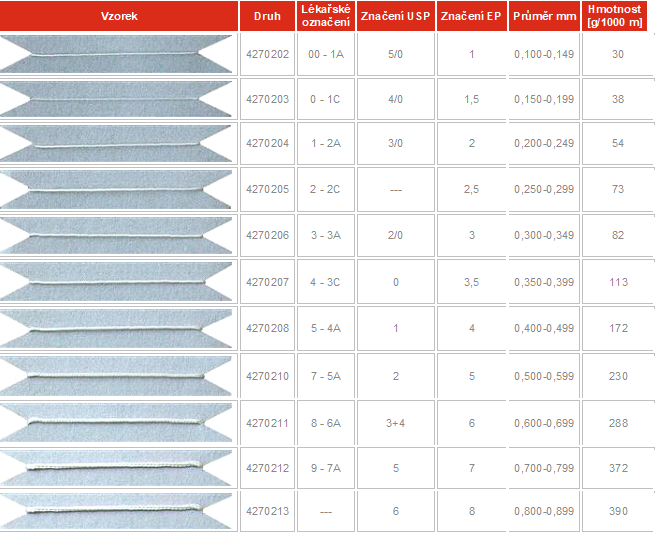

We categorize sutures according to the parameters listed in the following table:

RECOMMENDATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS FOR STERILIZATION

Procedures of sterilization and storage of surgical sewing materials from PAD6 and PES are identical and are determined according to valid European legislation.

These products are classified within the meaning of Government Regulation No. 336/2004 Coll. as an invasive inactive implant group IIb. and are labelled according to valid European legislation as non-sterile and nonabsorbable surgical sutures.

Their sterilization will be ensured according to ČSN EN ISO 11137-1: 2006 – Sterilization of Healthcare Products – Radiation Sterilization – Part 1.- Requirements for Development, Validation and Continuous Control of Sterilization Procedure for Medical Devices and according to ČSN EN ISO 11137-3: 2006 – Sterilization of Health Care Products – Sterilization by Radiation – Part 3 – Instructions for Dosimetric Aspects in a Special Radiation Centre. The standard sterilization dose is 25 kGy.

Properly packaged

remains sterile for 6 months.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR STORAGE

MANUFACTURING PROCESS

Surgical sutures are used to seal wounds and sew various cutting wounds or repair damaged tissue. There are many surgical sutures with different properties suitable for various applications. Surgical sutures are divided into two main groups:

absorbable

nonabsorbable

The absorbable materials degrade in the body. They degrade when the wound or cut is healing.

Non-absorbable materials resist attempts of the body to dissolve them. Nonabsorbable materials can be removed by the surgeon after the wound is healed.

Surgical sutures are made from both natural and synthetic materials. Natural materials are, for example, silk, flax and catgut, which is essentially dried and modified gut of a cow or a sheep.

Synthetic sutures are made from various textile yarns such as Polyamide (Nylon) and Polyester made especially for medical purposes. Absorbable synthetic surgical sutures are made especially from polyglycolic acid and glycol polymers. Majority of synthetic sewing materials have their own names like Dexon or Vicryl. Waterproof Goretex was also used as a surgical suture as well as thin metal wires.

Surgical sutures are also divided according to their form. Some are monofilaments, a form consisting of a single fibre – a line. Others consist of several filaments twisted or knitted together. Surgeons choose the appropriate type of suture according to the type of surgery. Monofilament allows what is called low tissue resistance, which means that the monofilament passes through the tissues very easily. Knitted or rolled surgical sutures show greater tissue resistance, but they are more easily knotted, and they have higher strength than knots on monofilament stitches. Knitted sutures are usually surface treated to reduce tissue resistance. Other sutures have knitted or rolled core with fine braid of extruded material, are known as pseudo-monofilaments. Sutures are also divided according to the diameter of the yarn. In the US, the USP scale is used, decreasing from 10 to 1 and then from 1-0 to 12-0. Surgical Sutures Control is under the FDA, as surgical sewing is classified as medical device. Production guidelines and testing for industry use are provided by the non-profit, United States Pharmacopeia, non-governmental agency located in Rockville, Maryland. In Europe, on the contrary, the EP rising scale is used, from 0.05 to 8. EP is the abbreviation of the European Pharmacopoeia, which is administered by the State Institute for Drug Control in the Czech Republic. (www.sukl.cz)

RECOMMENDATIONS AND INSTRUCTIONS FOR STERILIZATION

Surgical sutures are used to seal wounds and sew various cutting wounds or repair damaged tissue. There are many surgical sutures with different properties suitable for various applications. Surgical sutures are divided into two main groups:

absorbable

nonabsorbable

The absorbable materials degrade in the body. They degrade when the wound or cut is healing.

Non-absorbable materials resist attempts of the body to dissolve them. Nonabsorbable materials can be removed by the surgeon after the wound is healed.

Surgical sutures are made from both natural and synthetic materials. Natural materials are, for example, silk, flax and catgut, which is essentially dried and modified gut of a cow or a sheep.

Synthetic sutures are made from various textile yarns such as Polyamide (Nylon) and Polyester made especially for medical purposes. Absorbable synthetic surgical sutures are made especially from polyglycolic acid and glycol polymers. Majority of synthetic sewing materials have their own names like Dexon or Vicryl. Waterproof Goretex was also used as a surgical suture as well as thin metal wires.

Surgical sutures are also divided according to their form. Some are monofilaments, a form consisting of a single fibre – a line. Others consist of several filaments twisted or knitted together. Surgeons choose the appropriate type of suture according to the type of surgery. Monofilament allows what is called low tissue resistance, which means that the monofilament passes through the tissues very easily. Knitted or rolled surgical sutures show greater tissue resistance, but they are more easily knotted, and they have higher strength than knots on monofilament stitches. Knitted sutures are usually surface treated to reduce tissue resistance. Other sutures have knitted or rolled core with fine braid of extruded material, are known as pseudo-monofilaments. Sutures are also divided according to the diameter of the yarn. In the US, the USP scale is used, decreasing from 10 to 1 and then from 1-0 to 12-0. Surgical Sutures Control is under the FDA, as surgical sewing is classified as medical device. Production guidelines and testing for industry use are provided by the non-profit, United States Pharmacopeia, non-governmental agency located in Rockville, Maryland. In Europe, on the contrary, the EP rising scale is used, from 0.05 to 8. EP is the abbreviation of the European Pharmacopoeia, which is administered by the State Institute for Drug Control in the Czech Republic. (www.sukl.cz)

History

Doctors have been using sutures for at least 4,000 years. Archaeological records of ancient Egypt show that Egyptians used flax and animal tendons to close wounds. In ancient India, doctors used beetles and ants to close wounds. They placed these living creatures on edges of the wound, so that these creatures would squeeze the edges of wound with their pieces, then the doctor removed the bodies of the beetles, and the pieces stayed in place and held the wound closed. Other natural materials used in the old days were flex, hair, grass, cotton, silk, pork bristles and animal guts.

Although the use of surgical sutures was widespread, sutured wounds often became inflamed. The nineteenth-century surgeons preferred to burn the wound, which was often a terrifying process, before sewing with the risk of infecting the patient and death. Well-known English physician Joseph Lister discovered disinfectants in the 1960s, making surgery much safer. Lister dipped sutures from the catgut in phenol which sterilized them at least on the surface. Lister spent more than 10 years experimenting with catgut to find a material that would be flexible, strong, sterilizable, and absorbable in the human body in an adequate amount of time. The German surgeon made advances in catgut processing at the beginning of the twentieth century, leading to really sterile material.

Catgut was basic absorbable suture material in the 1930s, while doctors used silk and cotton when there was need for non-absorbable material. Technology of surgical stitching progressed with the formation of polyamide (nylon) in 1938 and polyester at similar time. As artificial textiles have been developed and subsequently patented for surgical stitching, sewing needle technology has advanced. Surgeons began to use atraumatic needles which were stitched to the surgical suture. This technique saved the need for threading the suture into the needle directly in the operating room and also allowed the diameter of the needle to be comparable to the diameter of the surgical yarn. In the 1960’s, chemists developed new synthetic materials that could be absorbed by the human body. These were polyglycolic acids and polylactic acids. First, absorbable suture material was made of natural catgut material. Nowadays synthetic absorbable sewing materials are used more than a catgut.

The FDA began to require the approval of new sewing materials at the beginning of the 1970’s. In 1976, the Medical Equipment Changes Division was added, and surgical stitching manufacturers have since been forced to seek product approval before launching. Manufacturers must adhere to the “Good Manufacturing Practices” rule and ensure that their products are safe and effective. Patents for new sewing materials are then valid for 14 years.

Raw materials

Natural sewing materials are made of catgut or dissolved collagen, or cotton, silk or flax. Many countries no longer accept catgut or collagen for sewing because of problems with animal protein products. Synthetic absorbable sutures can be made from polyglycolic acid, polylactic acid or polydioxanone, glycolide copolymer and trimethylene carbonate. These different polymers are marketed under specific brand names. Synthetic nonabsorbable surgical sutures can be made of polypropylene, polyester, polyethylene terephthalate, polyamide, various nylon types, or goretex. Some surgical sutures are made of stainless steel.

Surgical sutures are often coated, especially the knitted or rolled ones. They can also be dyed to be more distinct during the sewing process. Only the FDA approves the dyes and coatings that can be used. Certain approved dyes are: logwood extract, chromium-cobalt-aluminium oxide, ferro-ammonium pyrogallol citrate, D&C Blue No.9, D&C Blue No.6, D&C Green No.5 and D&C Green No.6. The coating used is chosen depending on whether it is absorbable or nonabsorbable suture.

The absorbent suture contains Poloxamer 188 and calcium stearate with polyglycolic copolymer. Nonabsorbable suture can be coated with wax, silicone, fluorocarbon or polytetramethylene adipate.

Surgical needles are made of stainless steel or carbon steel. Needles can be nickel-plated or electroplated. Packaging materials include waterproof foil such as aluminium foil as well as cardboard or plastic.

Design

MANUFACTURING PROCESS

The manufacturing process of surgical sutures does not differ very much from that of other synthetic textiles. The raw material is polymerized and the polymer subsequently extruded into a fibre. The fibre/yarn is stretched and knitted on knitting machines, which are also found in factories manufacturing polyester yarns for the garment industry. The production process usually takes place in three factories. One factory manufactures surgical fabrics, the other produces needles and the third factory, called finishing, joins needles and stitches together, packs them and sterilizes.

The first step in making surgical sutures is to create crude polymer. Workers will measure certain number of chemicals to produce the polymer in chemical reactor. In the reactor the chemicals are combined (polymerized) and extruded from the reactor in the form of small pits.

In the next step, workers throw the pits into the extruder. The extruder has a nozzle that looks like a showerhead that has many small holes. The machine melts the polymer, and this melt flows through the small holes, forming many individual filaments.

After extrusion, the filaments are tensioned between the two rollers. The filaments stretch up to five times their original length.

Some sutures are made as a monofilament. Others are knitted or rolled. For the preparation of knitting, the extruded monofilament must be reeled onto spools, which are then attached to automatic knitting machines. Such machines are usually of non-modern design and can also be used in the manufacture of garments. The number of filaments weaving together depends on the width of the resulting surgical suture of the particular type. Very fine sewing consists of 20 filaments, medium sewing of hundreds and very thick stitching consisting of thousands of twisted filaments. The knitting machine produces an endless strand of knitted material. Knitting happens very slowly and the machine usually runs 4 weeks non-stop. The process is almost completely automatic. Workers at the factory check the machines for a fault, replace empty spools for full, but generally the manufacturing process requires very little human work.

After knitting, surgical sutures passes through several stages of secondary processing. Sutures that were not knitted also pass through these phases directly after extrusion and primary stretching. Workers place the material on another machine to ensure further tensioning. Compared to the first stretching, this process can take only a few minutes and stretches the material by only 20%. The sewing then passes through hot roller, and any lumps, hairs and tiny flaws are thus ironed.

In the next step, workers put surgical sutures through an annealing furnace. The annealing furnace exposes the sutures to high temperature and stitching, which essentially compares the crystalline structure of polymer fibres into one long chain. This step may take several minutes or several hours, depending on the type of surgical suture being made.

After annealing, sutures can be coated. The coating materials vary depending on the material from which the suture is made. Suture passes through the bath of the coating material, which may be in the form of a solution or in thick pasty state called slurry.

All major manufacturing steps at the processing plant end at this point. Now staff of the Quality Control Department test the produced batch from many different qualitative points of view. Workers make sure that suture matches the width, length and strength of the European Pharmacopoeia of the EP or the American Pharmacopoeia of the USP, looking for physical defects and testing the solubility of absorbable sutures on animals and in tubes. If the batch passes all of these tests successfully, it is packaged and sent to the finishing plant.

Surgical needles are manufactured in another plant and are also dispatched to the finishing plant. Needles are made of fine steel and are drilled longitudinally. Workers in the finishing factory shorten sutures to standard lengths. The surgical suture is then mechanically inserted into the hole in the needle and the needle is threaded to the suture. The process is called swagging.

Subsequently the suture attached to the needle is placed in plastic bag and sterilized. Sterilization varies according to material of suture. Some sutures are sterilized by gamma-radiation. In this case, suture is completely wrapped. The whole package, usually sealed plastic bag inside the cardboard box, is inserted on the treadmill. The closed package is moved under the lenticular lenses that emit gamma radiation. This process kills all microbes. Suture is now ready for shipping. Some sutures do not withstand gamma radiation and must be sterilized in a different way. Sutures and needles are packed in plastic bag, but the bag remains open. Bags are moved to gas sterilization chamber filled with ethylene oxide gas. Then the plastic bags are closed, put into boxes or into other packs and are ready to be shipped.